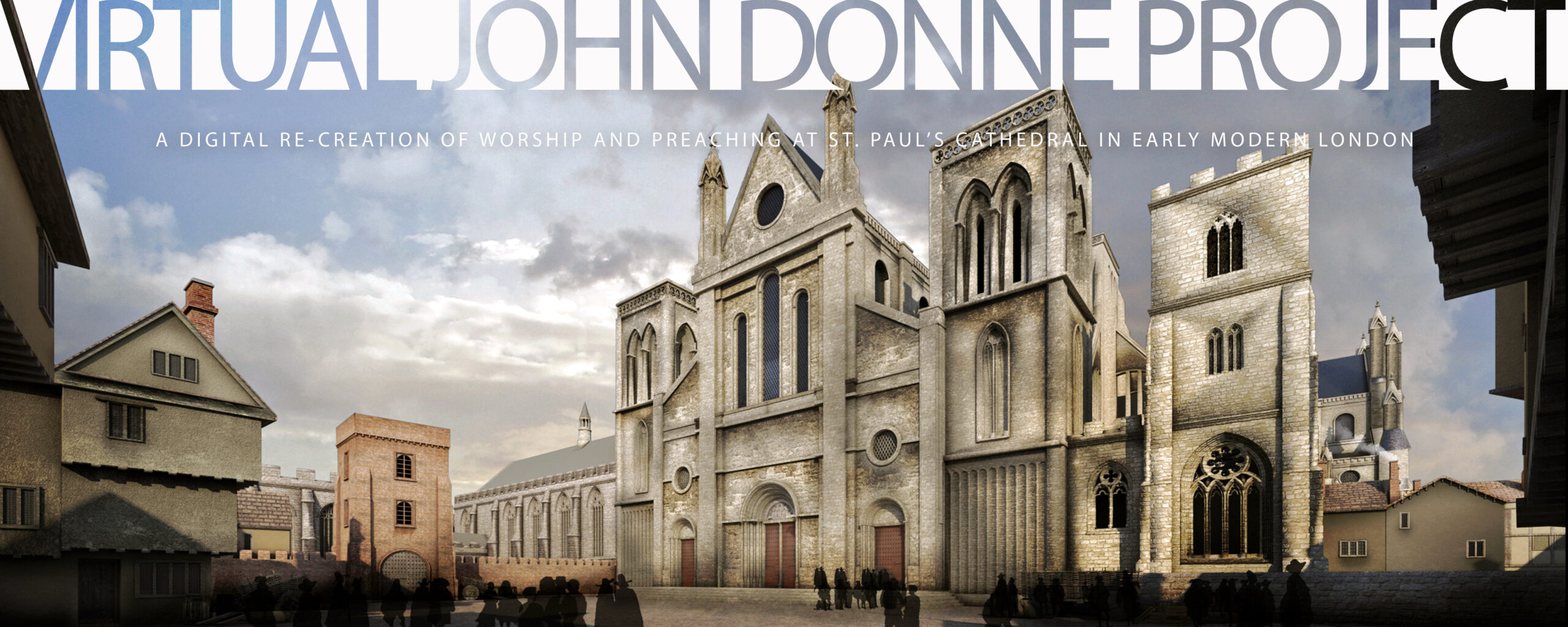

The Virtual John Donne Project uses digital modeling technology to enable users to explore the lived religion of England in the early seventeenth century. Our goal is to recreate worship services in the specific settings of their original performance so they may be experienced as they unfold in real time.

While theological controversies of the day were debated in reasoned statements of doctrine among the learned, to the vast majority of the English the reformed Church of England was defined primarily by the occasions of corporate, liturgical, and sacramental worship they participated in and were formed by. These services brought the private events of their lives — from birth to marriage to death — into the realm of public life.

Or, as church historian John Booty has put it, “In the parish churches and in the cathedrals the nation was at prayer, the commonwealth was being realized, and God, in whose hands the destinies of all were lodged, was worshiped in spirit and in truth.”

John Donne – Dean, St. Paul’s Cathedral, London

The Virtual John Donne Project addresses the issues of lived religion by using digital modeling technology to explore, in their public setting, events in the early years of John Donne’s career as Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral.

John Donne was elected and installed as Dean of St Paul’s on November 22nd, 1621. He remained as Dean until his death on March 31st, 1631. Donne had been ordained Deacon and Priest of the Church of England by the Rt Rev John King, Bishop of London, in the Bishop’s Chapel adjacent to the Cathedral on January 23rd, 1615.

As part of his responsibilities for maintaining the daily round of worship services at the Cathedral, Donne was assigned to preach inside the Cathedral at major festivals of the Church Year. He was also called upon to take part in the rotation of preachers at Paul’s Cross, outside the Cathedral, as well as on special occasions before other congregations.

Use the links provided below to navigate to three projects that combine visual and acoustic modeling to explore sites and events in Donne’s ministry during his time as Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral. To return to this page at any time, click on the NAVIGATION tab found on each of these three sites.

The essays and other resources found below demonstrate how these visual and acoustic models serve as research tools, enabling us to draw on our experience of worship and preaching in and around St Paul’s Cathedral in our discussions of Donne’s career as Dean.

While traditional approaches to understanding the nature of the English Reformation seek to understand reformed worship as expressions of the theology of the Reformers, use of these models enables us to reverse this relationship.

These sites give us access to the experience of early modern public worship that provide us a context for our study of the expressions of reasoned doctrine its participants authored, inspired, or objected to.

Using these sites, we are able to immerse ourselves in experiences of worship facilitated by use of the 1604 Book of Common Prayer. Our experience then becomes the necessary prelude to our interpreting early modern theological reflection on those experiences.

This site also serves as a repository of links to other online resources for the study of early modern London. To gain access to these links, click on the RESOURCES tab above.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Choir Screen. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

HISTORY OF THE VIRTUAL JOHN DONNE PROJECT

The origins of the Virtual John Donne Project lie in a graduate seminar I took at Harvard University in the fall of 1969. Taught by Herschel Baker and entitled “Religion and Literature from More to Milton,” this course brought the cultural and literary components of the English Renaissance together with the intellectual controversies of the English Reformation. The basic components of the Virtual John Donne Project emerged gradually in my own scholarly work as a graduate student at Harvard and as a young faculty member at North Carolina State University. My early work focused on the publications of the English Reformers, including the official documents of the emerging Church of England, and the literature on religious topics written by people who were influenced by the Book of Common Prayer, the English Bible, and the Books of Homilies.

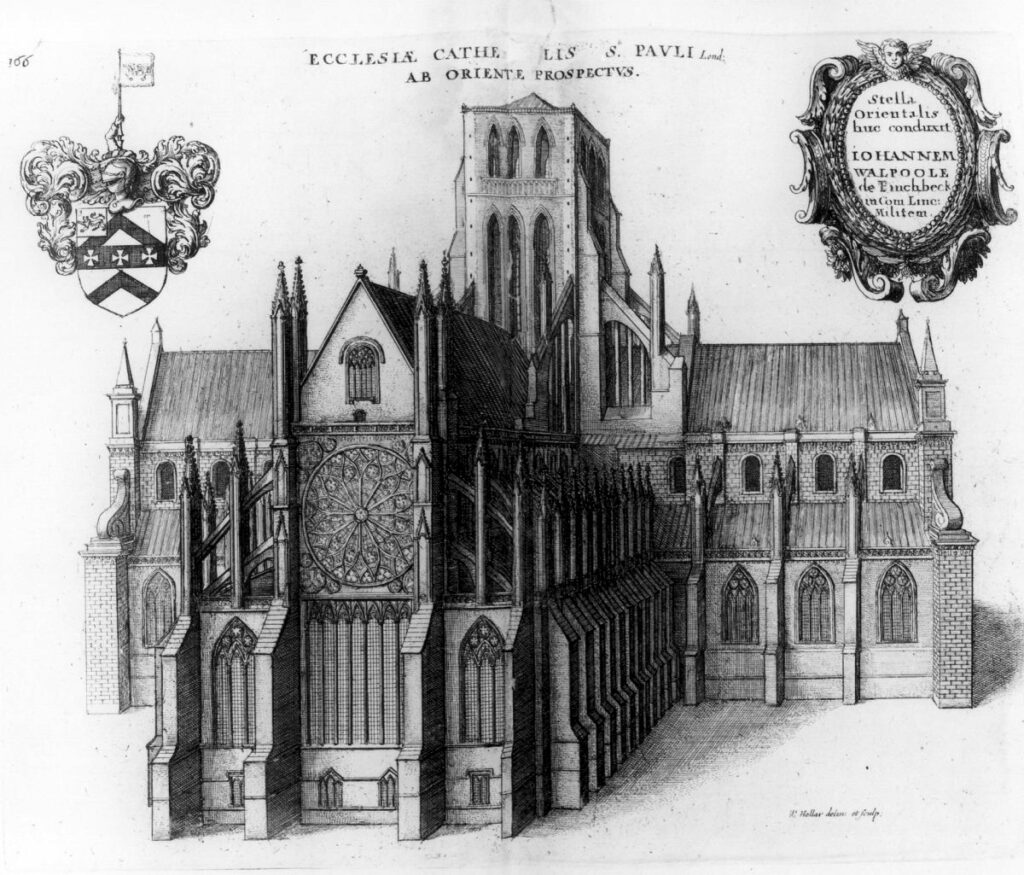

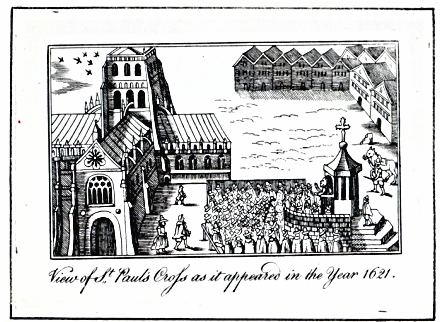

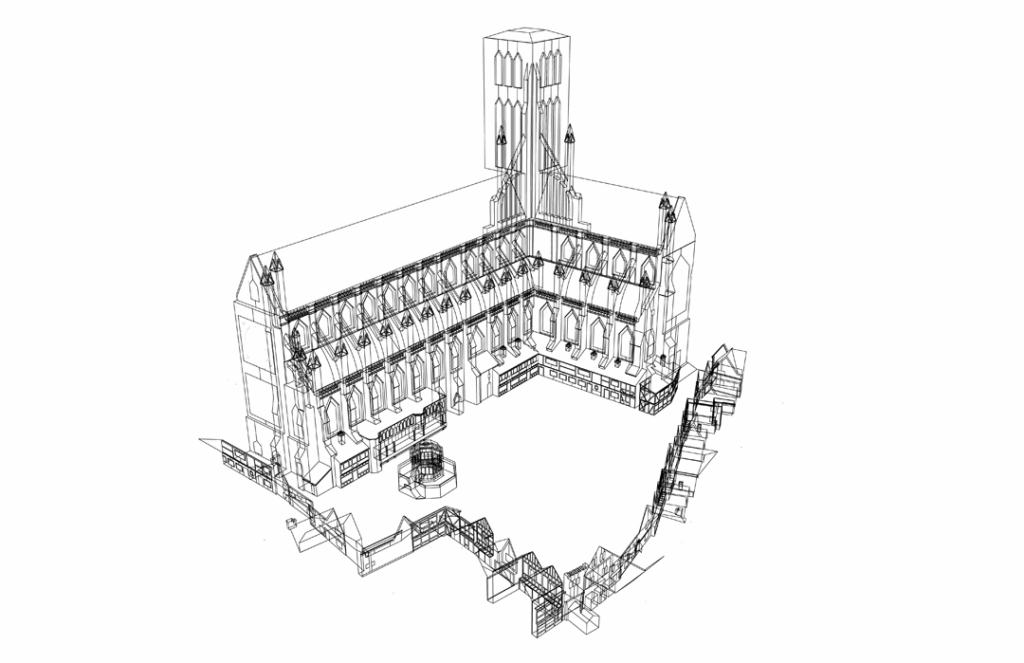

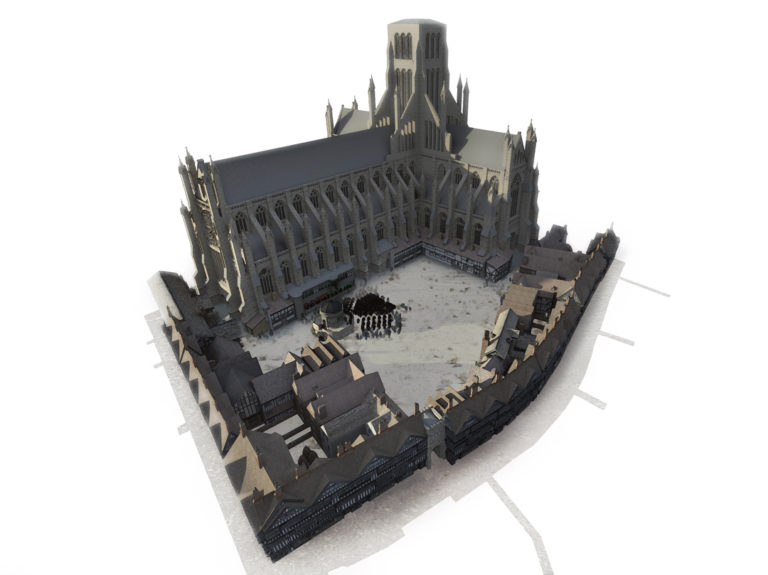

The series of images below illustrate the transitions we made in developing our visual models. We started, of course, with early modern images of St Paul’s Cathedral and its courtyard and moved on to the wireframe version and, step by step, to increasingly more detailed images.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the East Front, by Wenseslaus Hollar. Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Along the way and especially through developing friendships with faculty members in NC State’s College of Design, I became aware that digital modeling was being used by architects to design new buildings. I had become interested in John Donne’s years as Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral and and aware of Wenseslaus Hollar’s engravings of the Cathedral itself. It occurred to me that the digital modeling programs my Design colleagues were using could also be used to recreate a model of a building that no longer existed.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the East Front, drawing by Wenseslaus Hollar. Image courtesy Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University.

Happily, while this project was ongoing, Hollar’s original drawing of the Cathedral’s East End (see above) turned up to further enrich our sources for images of the building.

Over time, my own personal efforts to understand the very public culture of the reforming Church of England and my exploration of the possibility of developing a visual model of Donne’s St Paul’s grew into a project that came to involve a large number of people. Among them were professional actors, theologians, linguists, historians, engineers, and acousticians. But the largest single group was made up of students in the Colleges of Design and Engineering at North Carolina State University and in Jesus College of Cambridge University. They, in the end, made the models, transformed the historical, archaeological, and visual data into visual and acoustic experiences, and provided for us these recreations of the time, space, and sound of worship and preaching in London in the early 1620’s. Without their time and talent the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist.

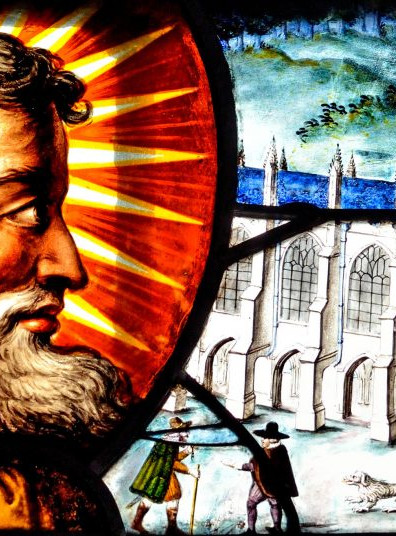

Paul’s Cross Preaching Station. Engraving courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Over the years of development for the Donne Project, several key moments stand out. A good number of important people happened to be nearby when I was telling folks the kind of project I was interested in developing. They expressed their interest, made suggestions about whom I should talk to, or said they could help with something. Their comments were timely, or led to other conversations, or turned into partnerships. Without their time and talent, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist.

The first of these was Bernard Frischer. From his work with the Rome Reborn Project, I was aware that lost buildings and landscapes could be recreated using visual modeling technology. I was also aware that there were a large number of images of medieval St Paul’s Cathedral that gave us information about how it looked before the Great Fire of London. So I met with Dr Frischer at the University of Virginia, showed him some of the historic imagery of St Paul’s Cathedral, and asked him how well he thought the data I had lent itself to the kind of project he had pioneered with Rome Reborn.

Wireframe Image of the Acoustic Model, Paul’s Churchyard, the Cross Yard. Wireframe from the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens.

“Yes,” Dr Frischer said, “you can do that.” But then he changed the entire scope and ambition of the Project when he added, “And you can hear it too.” And then he spent the rest of our meeting introducing me to the technology of acoustic modeling. especially how acoustic modeling could recreate the acoustic qualities of historic spaces, so that recording of sounds made today could be experienced as though they were being made and experienced in recreations of spaces that had not existed for hundreds of years. Without Dr Frischer’s guidance, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist.

With this transformed model for the project, my next major contact was David Hill, then a young Assistant Professor of Architecture but now Professor and Head of the School of Architecture at NC State University. One day early in the history of the Project, I mentioned my idea of using virtual modeling tools to a long-time friend in the College of Design, who said that I needed to get in touch with David, because he knew all about these kinds of projects. And indeed, he did. David became a partner and co-Principal Investigator and friend and supporter — and contact person for a long list of graduate students in Design whose work you can enjoy as you explore all the components of the Virtual John Donne Project. Without David’s commitment, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist

Paul’s Churchyard, the Cross Yard. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

The officers at the National Endowment for the Humanities were always helpful, especially Jason Rhody, who one day, while I was consulting him about why we were having trouble getting funding from the NEH, suggested that I was going about the application process the wrong way, that I should carve out of the larger project a smaller one, a “proof of concept” project, that would require less funding but would demonstrate the power of the technology we wanted to use. I immediately thought of what became the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project, which earned us our first NEH grant. We ultimately received both a digital humanities start-up grant and a digital humanities implementation grant, which together totaled $375,000 in funding. Without Jason’s help, and the funding from the NEH it led to, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist.

The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project required the script of a sermon John Donne delivered at Paul’s Cross. Seeking authenticity, I contacted the linguist David Crystal, who graciously agreed to prepare a script for us in early modern London dialect. And then, when I asked him if he knew any actor who was good at using this dialect, he suggested his son Ben Crystal, who played the role of Donne the Preacher for both the Paul’s Cross and the Cathedral Projects. Without David and Ben, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist.

Paul’s Cross, from the Sermon House. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project also required acoustic engineers who could take Ben Crystal’s recording of Donne’s sermon made in an anechoic chamber to eliminate any traces of the space in which the recording was made and auralize it so that it would sound like it had been delivered in Paul’s Churchyard. When I had trouble finding such a person, my friend John Randell suggested I contact his friend Ben Markham, of Acentech, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. And so Ben and his colleague Matt Azevedo produced a version of Ben’s recording for the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project that enables us to hear it from 8 different listening positions and in the presence of 500, 1200, 2500, and 5000 people. Without Matt and Ben, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist.

Paul’s Cross from 25 feet. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

Along the way, I was introduced to John Schofield, who at the time was polishing up the manuscript for his epic work St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren (2011), a volume that contains practically everything we can know about pre-Fire St Paul’s from the archaeological and visual record. John supported us through thick and thin. Without John’s vast knowledge of the cathedral and of early modern London and his generosity of spirit in sharing his great learning, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist.

As we got more deeply into the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project, we recognized our need for a choir. I had already been in touch with Roger Bowers of Jesus College, Cambridge, about choosing the repertoire for the choral performances. Happily, Roger introduced me to Richard Pinel, then Choirmaster of Jesus College, and his organists and singers performed admirably in their roles. Ben Crystal, reprising his role as John Donne, also put us in touch with the Shakespearian actors Colin Hurley and William Sutton to play the roles of clergy at St Paul’s. David Crystal played the role of Lancelot Andrewes. Without their help, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist.

Paul’s Churchyard, from the southeast. From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

Once we had all the recording done, we discovered the NEH would no longer support our use of commercial acoustic engineering firms, so we needed an in-house acoustic engineer to auralize over six hours of recordings. Happily, Yun Jing had just been hired by the College of Engineering at NC State, so he took over that role. He became a third co-Principal Investigator, and with his graduate students auralized all the recordings and also developed an open-source acoustic modeling program, openly available for download from the Virtual Cathedral’s website. Without Yun Jing’s help, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist.

The final editing of the sound was done at NC State by Neal Hutcheson, a member of the staff of NC State’s Linguistics faculty. Without Neal’s help, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist.

Trinity Chapel in 1623. Rendering by Jack McManus.

Guy Holborn, then Archivist at Lincoln’s Inn, gave me access to archival material that went into recreation of Trinity Chapel on the day of its Consecration, May 22, 1623. Without Guy’s assistance, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist. When we started work on the reconstruction of Trinity Chapel, we became indebted to two additional students in NC State’s College of Design — Trevor Healey, who designed the website, and especially to Jack McManus, who created the renderings of Trinity Chapel as it looked in 1623. Without Trevor’s and Jack’s assistance, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist.

Trinity Chapel, looking Northward. Rendering by Jack McManus.

We have also benefitted from an active and supportive Advisory Committee, the members of which have changed somewhat over the years, but have included Diarmaid MacCulloch, Gordon Higgott, Damian T. Murphy, Jeanne Shami, Arnold Hunt, Mary Morrissey, Emanuela Vai, Roze Hentschell, Mary Ann Lund, and the great pioneer of work in the digital humanities, Willard McCarty. Without their efforts to keep us in the right track as these projects moved forward, the Virtual John Donne Project would not exist.

As I look back over the years of work that went into all the components of the Virtual John Donne Project, I feel humbled that so many distinguished folks gave so much of their time and expertise to its success. This was truly a collective effort, the work of many hands. Being a part of it has been the highlight of my career in the academy.

John N. Wall Professor of English Literature Emeritus, North Carolina State University

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Visual Model. Rendered by Austin Corriher.

DIGITAL DONNE — Resources from the John Donne Society — http://johndonnesociety.org/sites.html

COMPONENTS OF THE VIRTUAL JOHN DONNE PROJECT

Paul’s Cross Project

The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project provides the experience of hearing John Donne’s sermon for Gunpowder Day, November 5th, 1622 in Paul’s Churchyard, the specific physical location for which it was composed.

The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project helps us to explore public preaching in early modern London, enabling us to experience a Paul’s Cross sermon as a performance, as an event unfolding in real time in the context of an interactive and collaborative occasion.

Trinity Chapel Project

The Virtual Trinity Chapel Project reconstructs the Service of Dedication conducted by the Rt Rev George Montaigne, Bishop of London, during which Donne preached. Drawing on original documents and contractors’ bills, it also reconstructs the original interior of this building.

John Donne served as the Reader in Divinity at Lincoln’s Inn in London from October 24th, 1616 until February 11th, 1622. Donne was recalled to Lincoln’s Inn on May 22nd, 1623 to preach at the consecration of the Inn’s new chapel.

St. Paul’s Cathedral Project

The Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project enables us to experience worship and preaching at St Paul’s Cathedral as events that unfold over time and on particular occasions in London in the early seventeenth century.

Events featured on this site include two full days of services. A festival day — Easter Sunday 1624 — includes sung Matins; the Great Litany; Holy Communion, with a sermon by Bishop Lancelot Andrewes; and Evensong, with the sermon preached that day by John Donne, Dean of the cathedral. A ferial, or ordinary day — the Tuesday after the First Sunday in Advent, 1625 — includes Matins and Evensong.

Donne Online

St Paul’s Cathedral, the East Front. Image by Smith Marks, Rendering by Austin Corriher

FINIS