Edit with Elementor

Loading

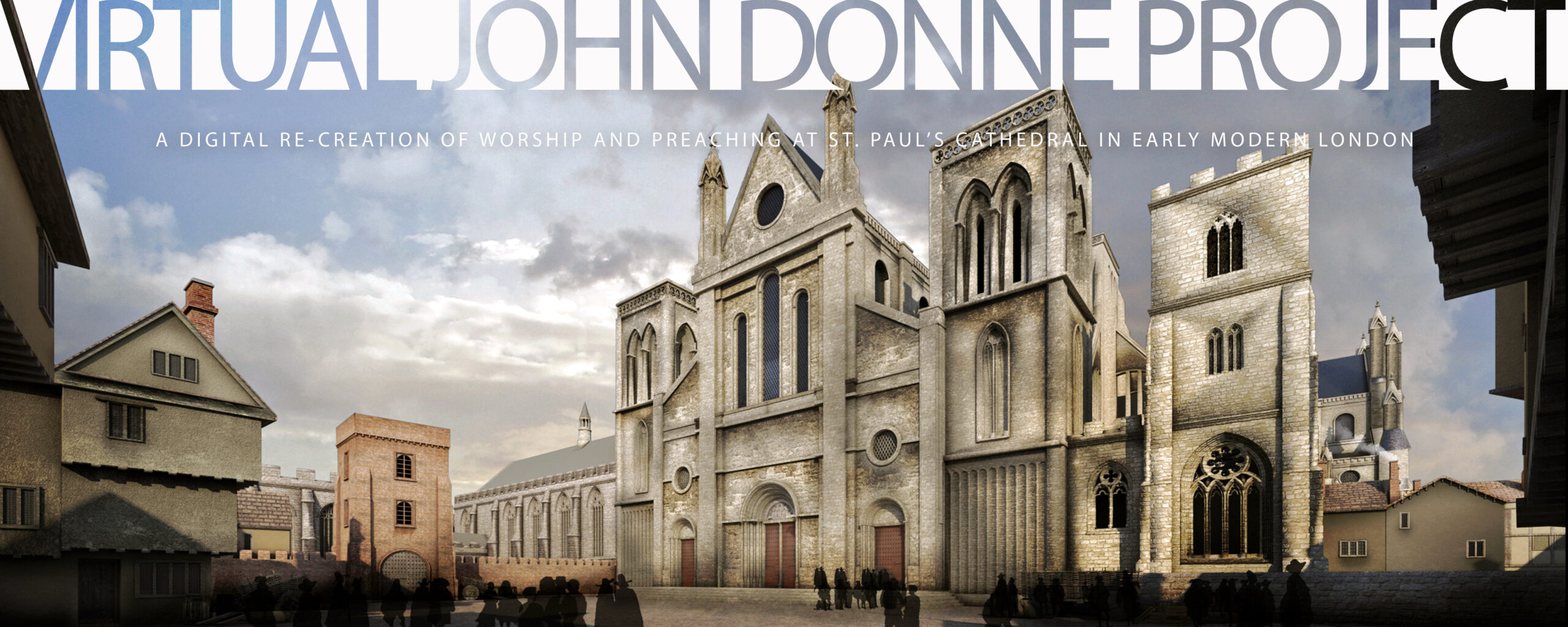

St Paul’s Cathedral from the Southwest. Image by Smith Marks, Rendering by Austin Corriher

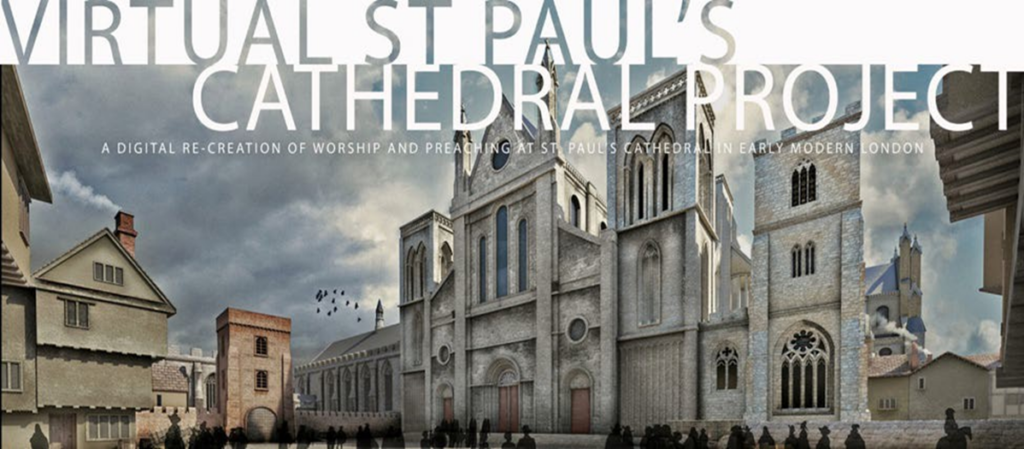

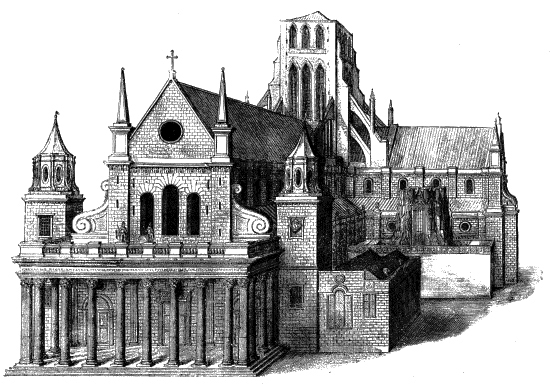

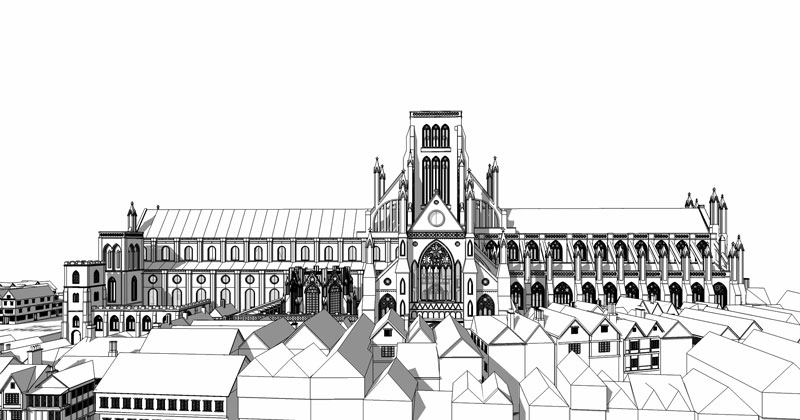

The Virtual John Donne Project is in part about recovering sites and sounds of buildings and spaces that were significant in the career of John Donne as priest in the Church of England and Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral, from 1621 to his death in 1631. So this work is about recovering not only the look but also the the experience of what has been lost to us. The buildings modeled in the Paul’s Cross and St Paul’s Cathedral Projects were of course destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666. Trinity Chapel survives, but not in its original configuration, either externally or internally.

That is work worth doing, but only if it then leads to interpretive work that helps us understand more fully Donne’s role in these spaces. Donne was not a systematic theologian. Scholars who treat him as such abstract a coherent system of theological understanding from his sermons and other writings. But the Cathedral Project websites help us to recognize that Donne’s sermons preached in and around St Paul’s were composed for specific places and occasions that would have been scripted by the texts of services in the Book of Common Prayer with their routine of the Daily Offices and the specific occasions of the celebration of Holy Communion.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Nave, looking East. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Coriher.

Each of these services had its prescribed set of readings from the Book of Psalms, the other books of the Hebrew Bible, and the books of the New Testament. Each had its prayers, canticles, and other prescribed texts that were repeated at every service or were varied with the weeks of the Christian Church Year. In addition, Donne’s non-homiletic writings assume that his audience would recognize references to this cycle of rites and readings. One thinks of Donne’s references in his Devotions upon Emergent Occasions to the sounds of church bells that marked the time or called people to worship. Or his description of the sounds of the Cathedral’s Choir chanting the Psalms for the day, or the Cathedral’s clergy making pastoral calls on their Dean in his sick bed.

The websites gathered under the umbrella site The Virtual John Donne Project enable us to experience the Cathedral’s working day, providing us with performances of two of Donne’s sermons — and one of Lancelot Andrewes — within their original liturgical contexts. With this assistance we can glimpse the liturgical occasions for his preaching, the ritual envelope for his contribution, the public environment within which his preaching took its place in conversation with the worship going on around it.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Choir from the East. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher

The new Oxford edition of Donne’s sermons (https://donnesermons.web.ox.ac.uk/), with its gathering of Donne’s sermons chronologically and by the location of their delivery, supports our attending to the conditions, both acoustically and contextually, of their delivery. By using the Virtual Donne websites in coordination with this unfolding edition, we can engage in our own interpretive work by placing Donne’s writings from this period in his life in the context of the spaces and occasions in which he worked and lived in the last ten years of his career.

What follows are my efforts to begin that process.

SECTION ONE: ESSAYS BUILDING ON THE VIRTUAL JOHN DONNE PROJECT

ESSAY 1. Materializing Lost Time and Space: Implications for a Transformed Scholarly Agenda

This essay was written as part of the development of the website that contains it.

The websites clustered under the umbrella site The Virtual John Donne Project enable us to experience worship and preaching in London in the early 1620’s as events that unfold in real time and in the liturgical contexts and physical spaces in which they were originally performed. The purpose of these sites is to make possible the study of lived religion in early modern London. “Lived religion” is a term that some scholars of religion use to distinguish the subject of their study from a focus on cognitive matters — on creeds, for example, or on formal statements of belief, or on the content of theological treatises. Lived religion is the study of what one practitioner has described as “the forms of action by and through which a religious tradition, church, or community works out the nature and boundaries of what it is to be religious.”

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Choir from the West. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

The Websites

The content of the Virtual John Donne Project gives us access to the lived religion of London because it recreates worship services that took place both inside St Paul’s Cathedral (The Virtual Cathedral Project) and outside the Cathedral in Paul’s Churchyard (The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project), as well as the service of Consecration of Trinity Chapel at Lincoln’s Inn (The Trinity Chapel Project).

The worship services inside St Paul’s constitute the full liturgical day as scripted by the Book of Common Prayer, including Morning Prayer, or Matins, the Great Litany, Holy Communion, and Evening Prayer, or Evensong, required to be used on Sundays and Holy Days in all churches, chapels, and cathedrals in England from the middle of the 16th century until it was withdrawn from service by the Puritan party when it was victorious in the English Civil War of the 1640’s. Two of these four services – Morning and Evening Prayer – were required to be observed every day of the year. While the style of worship at St Paul’s – with its use of choir and organ — differed from the style found in one’s typical parish church, the rites themselves were the same.

The Paul’s Cross Preaching Station. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

On the Paul’s Cross Project’s website, we can experience John Donne’s Gunpowder Day sermon from 1622 as though we too were standing or sitting in Paul’s Churchyard for the full two hours of the sermon. We can also explore the question of just how well people could hear Donne’s sermon, by listening to it from several locations inside the Churchyard. On the Trinity Chapel website, we can explore the design of Trinity Chapel at London’s Lincoln’s Inn on the morning of the Feast of the Ascension in May of 1623 and the service of Consecration of the Chapel conducted that day by George Montaigne, Bishop of London. John Donne, former Preacher to Lincoln’s Inn, preached the sermon that day as part of the sequences of services – including Morning Prayer, the Great Litany, and Holy Communion – that inaugurated worship in the Inn’s new worship space. On the Cathedral Project website, we are able to experience the liturgical day in its festival form – Easter Day 1624 – when morning worship started at 10:00 and included three services, Morning Prayer, the Great Litany, and Holy Communion with a sermon of about an hour, as well the liturgical day in its ferial, or ordinary form, which included only Morning and Evening Prayer.

When we add up the time folks were required by law to be in church on Sundays and Holy Days, the total comes to three or so hours in the morning. Evening Prayer — also known as Evensong – began at 4:00 (probably moved to 3:00 in the shorter days of winter) and – when it was followed by a sermon, as it was customarily at St Paul’s — added another 2 hours of time in church on Sundays and Holy Days before it was done. For most of us, spending 5 hours in church on Sundays is difficult to imagine, but for Donne and his colleagues on the staff at St Paul’s, this was just another day at the office.

These Easter Day recreations give us the experience of worship on Sundays and Holy Days. To give the experience of all the other days of the year, we have included recreations of a ferial, or ordinary, day – a Tuesday after the First Sunday in Advent, a Sunday in late November of 1625. This day serves as a representation of every day in the year other than Sundays and Holy Days, with only the services of Morning Prayer in the morning and Evensong in the afternoon, each one lasting about three quarters of an hour.

Trinity Chapel, the West Front. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

The daily and weekly services of worship were, in turn, imbedded inside cycles of readings that continued throughout the seasons of the Church Year, beginning in Advent and running through Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, and Easter, until Trinity Sunday and the Sundays after Trinity, which brought worshippers back once more to Advent, when the cycle begins again. Each of these days has its own assigned readings of the Psalms, the chapters of each book of the Bible, and special prayers for specific Holy Days and occasions in the life of individual members of every congregation. Worshipping communities, following the Lectionary, read the Hebrew Bible through once a year, the New Testament three times a year, and the Book of Psalms once a month.

Clergy in the Church of England took – and still take – vows at their ordination to read – either with their congregations or on their own – Morning and Evening Prayer and the Lessons appointed for each day. In cathedrals these Daily Offices were conducted in the Choir, with musical settings of the Psalms and anthems. Clergy in parish churches might have read the Offices on their own, or, like George Herbert, read the Offices in their churches and invited their congregants to join them. The Canons of St Paul’s Cathedral took this discipline one step further; they divided the Psalms up among them so that, collectively, they read the entire Book of Psalms through every day.

The rites of the Prayer Book focus our attention on the public worship of the Christian community. Members found meaning in their lives through their participation in their local worshipping community. Instead of concerning themselves with the private and individualistic question of whether or not they were members of God’s Elect, worshippers took part in corporate worship, a rhythm of reading, proclamation, confession, absolution, affirmation, intercession, and communion, as very members incorporate in the “mystical Body of Christ, the blessed company of all faithful people, heirs through hope of God’s everlasting kingdom.”

Here, private and personal events over one’s lifespan took on meaning through being brought into the life of that community. Parents were required to bring their new-born children to church for Baptism in the first 5 days of their lives, then bring them to church for religious instruction on Sundays at Evensong in anticipation of the Rite of Confirmation, to receive Holy Communion at least 3 times a year, to be married in church, to be ministered in sickness by the local vicar acting on behalf of the congregation, and to be brought to church for one’s funeral and burial in consecrated ground.

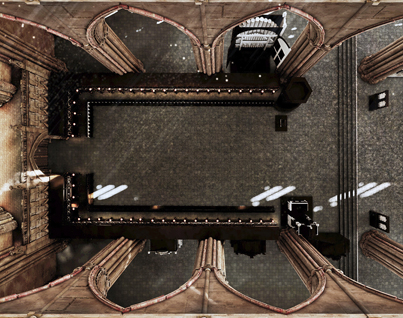

Trinity Chapel, the Choir from Above. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

Modeling Lived Religion

Taken together, the practice of Prayer Book worship created, enabled, and informed the lived religion of early modern England. But this is rarely acknowledged as significant when we as scholars turn our attention to the works of early modern religious writers. Sermons are treated as theological treatises, mined for their evidence for the theological leanings of the preacher rather than locating sermons in the context of worship services. Devotional works are read autobiographically, or in relationship to various genres and styles of religious writing, rather than in relationship to the ongoing worship life of congregations.

Sampling Lived Religion

To take but one example, John Donne’s classic devotional work the Devotions upon Emergent Occasions. Here, the scholarly consensus is that the Devotions gives us insights into Donne’s personal biography, his own spiritual progress through his illness in the fall of 1623, his inward journey from sickness to health, offered as an example for the private and inward journey of others. But, when one enters the work, one is immediately immersed into the cycles of worship and prayer, of the systematic reading of scripture, of the systems of communication among the faithful – in short, the world of lived religion. Donne hears the Choir of the neighboring St Paul’s singing the Psalm; he is visited by other clergy who come to him to conduct the Prayer Book’s rites of ministry to the sick; he hears the bells of local parish churches ringing out messages about the lives of its parishioners and calling its members to worship. He draws on citations from the Apocryphal Book of Ecclesiasticus to inform his understanding of his illness, not because it is an especially appropriate source for comfort and understanding but because it is one of the books appointed by the Prayer Book lectionary for reading during late November and early December, precisely the time in which Donne was confined to his bed.

Consequences

Given this recognition of the corporate and communal lived religion of the Church of England in the early modern period, and given the ways the Virtual Donne websites give us access to early modern worship services as events that unfold for us in real time, as they did in the 1620’s, it is appropriate to ask how this understanding calls on us to reframe our scholarly study of early modern religious literature. What follows is chiefly concerned with sermons, but – as we have already seen from our glance at Donne’s Devotions – is also applicable to devotional writings as well.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Choir from Above. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

At its heart is the recognition that – whether in manuscript or printed form – what we think of as a sermon is a script for a performance, a rite of corporate participation, not primarily a theological treatise. A sermon takes place in the context of the performance of a larger script — the worship services scripted by the Prayer Book — that provides the context for preaching, whether or not a particular sermon was delivered in the context of a Prayer Book scripted service, an addendum to one of those services, or as a stand-alone lecture, because whoever was preaching that sermon was also reading the appointed Lectionary readings and participating in the performance of those services on a daily basis as he was preparing to preach that sermon. Indeed, the act of preaching, the performance of the sermon, was sufficiently understood to be so integral to the early modern concept of a sermon that many clergy in our period refused to have their sermons printed. In our study of them, therefore, sermons and devotional writings need to be located in the context of the terms, resources, and goals of the ongoing worship life organized, enabled, and supported by use of the Book of Common Prayer.

The Liturgical Context

Sermons – according to the Book of Common Prayer – were required on Sundays as part of Holy Communion, which followed Morning Prayer and the Great Litany on Sunday mornings. According to William Harrison, in his detailed description of worship in the Church of England, sermons also followed Evening Prayer. So the sermons John Donne preached at St Paul’s were among them. And, while some sermons were delivered more lecture-style – outside the formal context of Prayer Book worship, all sermons were prepared and delivered by clergy who were taking part in the ongoing cycles of scripture readings and worship created by the Prayer Book’s Lectionaries. So when we address our attention to a sermon, we need to do so by placing it in the context of the Biblical lessons read that day and at least the week before it was delivered. We need to know if the preacher drew on those texts in the development of his sermon (as Donne did in his Trinity Chapel sermon) as well as what light those Lectionary readings cast on the actual Biblical texts he chose to cite in the sermon.

The Text

At the same time, we need to recognize that what we have, and call a sermon, is likely to be something, at least potentially, quite different from what we are really interested in, which is the sermon delivered. What we have – whether in manuscript or in print – is an after-the-fact reconstruction of the sermon delivered. Many early modern preachers did not preach from complete drafts of their sermons, but from notes. The complete version they wrote down for themselves and perhaps for publication in the days and weeks after they had delivered it surely differed from the sermon delivered – either because of faulty memory of what was actually said, or because of second thoughts about what was said. Even if the preacher did work in the pulpit from a full draft of the sermon, he had the opportunity to revise the script before it went into his archives or to the print shop. Hence our awareness of the potential separation between the sermon delivered and the surviving draft of the sermon should alert us to the need to pay special attention to surviving aspects of the sermon that reflect most clearly the preacher’s awareness of and interaction with his congregation.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Choir from Above. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

The Congregation

Early modern sermons are to be considered as one side of a two-way conversation between clergy and laity. We must, therefore, pay attention to ways in which congregations took part in a worship service, whether by responding to prompts by the clergy – “The Lord be with you/And with thy Spirit,” for example – or by taking part in corporate recitations of longer parts of the service, such as the Lord’s Prayer, the Creeds, and the Confessions. So, who was in a particular congregation is worth knowing if we are fully to understand the sermon as we have it. The new Oxford edition of the sermons of John Donne recognizes this in the way the editors have chosen to group Donne’s surviving sermons in terms – not simply of chronology, as Potter and Simpson did the California edition of the 1950’s and early 1960’s – but of the sites in which Donne delivered them. So we have the sermons Donne preached in the Chapel Royal, before the royal court, the sermons preached at Lincoln’s Inn, the sermons preached at St Paul’s Cathedral or at Paul’s Cross, and so forth. In the process, the editors have helped us recognize differences among Donne’s sermons in terms of subject matter and style of composition that reflect differences in the composition of those congregations.

In addition, we need to pay attention to points in early modern sermons where the congregation is directly engaged, whether this be in the form of jokes, or of references to common experiences or points of reference, or, as Donne does at the end of a sermon from the late 1620’s, to the conventions of sermon delivery, in this case the hourglass that marked the time of the sermon as it was in the process of being delivered. We also need to pay attention to ways in which a given sermon takes its place in the larger liturgical framework of the worship service. So we are called to attend to the specific emphases of the Lectionary readings, the prayers, and other parts of the service unique to that day on the Church Calendar, as well as to our understanding of the overall didactic intent of liturgical worship, in the context of the historical moment in which the sermon was delivered.

One thinks of the opening words of Bishop Lancelot Andrewes, preaching at the Chapel Royal on Christmas Day 1610 – “There is a word in this text, and it is hodie, by virtue whereof this day may seem to challenge a special property in this text, and this text in this day. Christ was born, is true any day; but this day Christ was born, never but to-day only. For of no day in the year can it be said hodie natus but of this. By which word the Holy Ghost may seem to have marked it out, and made it the peculiar text of the day.”

Paul’s Churchyard, the Paul’s Cross Preaching Station. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

The Places

We must also consider the physical location of the sermon-as-event – the worship space inside a church building or – for sermons like the ones delivered in London at Paul’s Cross – the outdoor space, as well as the acoustic properties of that space, the size of the congregation in attendance, and the makeup of that congregation, in terms of social class, educational background, and the like. One of the more powerful recognitions we have come to is the fact that the sermons Donne preached at St Paul’s were heard by a congregation perhaps no larger than 50 people. Another concern for us needs to be consideration of the specific space in which a sermon was delivered. This would include the shape of the space, the acoustic properties of the space, the sight lines, and the location of the congregation in relationship to the preacher. We have been able to determine, for example, that – even without amplification — if the crowd was relatively quiet, people all across Paul’s Churchyard could hear the preacher of a Paul’s Cross sermon.

Conclusion

Attending to these concerns in our discussions of early modern religious texts will bring us closer to understanding how they were to work as part of worship, as part of the overall experience of Prayer Book Worship, making their own unique contribution to the experience of the day as well as taking their part in the larger worship process. Our challenge is to recognize more deeply that religious texts are at heart works performed to further the larger ends of worship. Sermons of course do contain discussions of theological issues but the point of a sermon is to be part of a service of worship that draws the congregation together, over a course of time, to be formed as community and to be enabled, inspired, and empowered to live the lives to which they are called as God’s people. This happens, not simply by hearing sermons preached on their own, but through the process of experiencing sermons preached in the context of worship services in which scripture was read and expounded, Creeds were recited and affirmed, confession was made and absolution received, prayers of intercession and thanksgiving were offered, and the bread and wine of Holy Communion was consumed, by means of which corporate action, as John Booty put it years ago in the Preface to his edition of the 1559 Book of Common Prayer, the nation was enabled to be “at prayer, the commonwealth was being realized, and God, in whose hands the destinies of all were lodged, was worshipped in spirit and in truth.”

St. Paul’s Cathedral, the West Front. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

ESSAY 2. “Stirred up to godliness (and) able also to exhort others by wholesome doctrine”: Enabling Lived Religion in Early Modern England

This paper was delivered at the Echoes Through Time: Perspectives on Sacred Space Acoustics Conference at Yale University in 2025

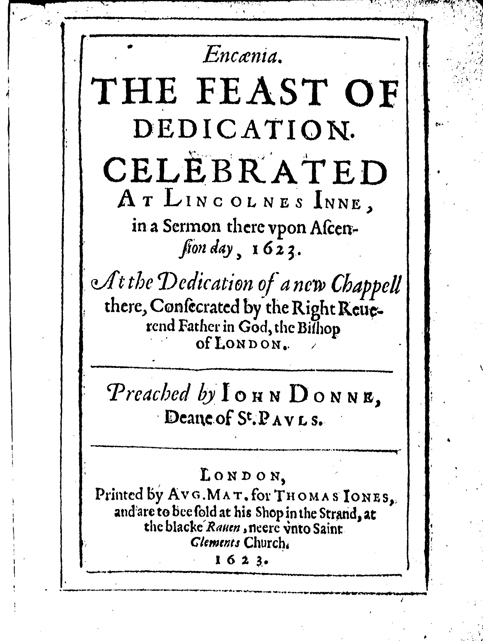

This essay builds on work with digital visual and acoustic modeling tools to recreate the experience of worship and preaching in various sites in early modern London, chiefly in and around St Paul’s Cathedral during John Donne’s tenure as Dean of the Cathedral from 1621 to 1631. Grouped together as the Virtual John Donne Project, this work recreates John Donne’s Paul’s Cross sermon for Gunpowder Day, November 5th, 1622 in Paul’s Churchyard; two full days of worship inside St Paul’s Cathedral from the mid-1620’s, with sermons by Donne and Lancelot Andrewes; and the service of consecration and dedication for Trinity Chapel at London’s Lincoln’s Inn, held on May 22nd, 1623.

These websites thus provide experiential resources for understanding worship in English cathedrals and parish churches in the early seventeenth century. Chief among them are visual depictions of St Paul’s Cathedral around 1625 ( and well before it was destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666) depictions are linked to auralized recordings of services appointed for use every day of the year — the Divine Services of Morning Prayer (Matins) and Evening Prayer (Evensong) — as well as services appointed for a narrower range of days — (the Great Litany, appointed for Wednesdays, Fridays, and Sundays and Holy Communion, appointed for Sundays and Holy Days).

These services recreate two full days in St Paul’s Cathedral — an ordinary (or ferial) day (that is, a day that is not a Wednesday, Friday, Holy Day, or Sunday), specifically the Tuesday after the First Sunday in Advent in 1625 and a Festival Day, Easter Sunday in 1624. These services reflect in the choice of music – whether survivals of medieval chant or compositions by contemporary composers like Orlando Gibbons, Thomas Tallis, or St Paul’s own Adrian Batten — and differences in style of performance that distinguish differences between a festival, or special, occasion and an ordinary, everyday occasion.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Choir, from the Pulpit. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

My argument here is for the value of adding the experience of the passage of time and their liturgical context to our consideration of the theological content of sermons, liturgies, and other religious discourses that come down to us from the early modern period. We now receive the works of Donne, Hooker, and other leaders of the English Reformation in hefty and handsomely bound volumes; while there is certainly gain in this, what is missing is the ephemerality of occasion and context, dimensions vastly more significant to their original participants. Donne’s sermon for Gunpowder Day in 1622, for example, was not part of a regular preaching obligation for Dean Donne but as the result of a specific request from King James I that he do so to defend the King’s authority in conducting foreign policy.

Over the past decade, the use of digital modeling has enabled those of us working on the various parts of the Virtual John Donne Project to restore the specifics of performance, physical setting and the passage of time to some of the occasion-specific texts that survive from the early modern period. Using digital humanities grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities – your taxpayers’ money at work — to support the work of over a hundred people — actors, linguists, historians, musicians, graduate students in architecture and acoustic engineering, and many others — all contributing in large ways and small, we have been able to recreate the experience of specific spaces and occasions otherwise lost to us.

Included on the website are recordings from our reconstruction of all the services of representative days of occasions of worship, including Morning Prayer, or Matins; the Great Litany, Holy Communion, and Evening Prayer, or Evensong. These contain both spoken and sung parts of all these services, heard from six different listening positions, to illustrate how the qualities of sound vary in volume and resonance from one physical location to another. This kind of work is especially important because — while the theological controversies of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were debated among the learned — to the vast majority of Englishfolk the reformed Church of England was defined by the occasions of corporate, liturgical, and sacramental worship they participated in through public performance of the liturgical texts contained in the Book of Common Prayer. From its very first edition in 1549, the Prayer Book enabled and defined the religious life of England, this “one use” bringing the nation together in common worship, promoting “wholesome doctrine” and the “advancement of godliness” through the “daily hearing of holy Scripture” and celebration of Baptism and Holy Communion in the language of the people.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Choir, looking East. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

The corporate experience of Prayer Book services thus sought to unite the nation, forming a deeper and truer sense of corporate religious identity and giving the private events of folk’s lives — from birth to marriage to death — a richer meaning through their linguistic and liturgical incorporation into the realm of English public life. Or, as church historian John Booty has put it, in admittedly idealistic terms, “In the parish churches and in the cathedrals the nation was at prayer, the commonwealth was being realized, and God, in whose hands the destinies of all were lodged, was worshiped in spirit and in truth.”

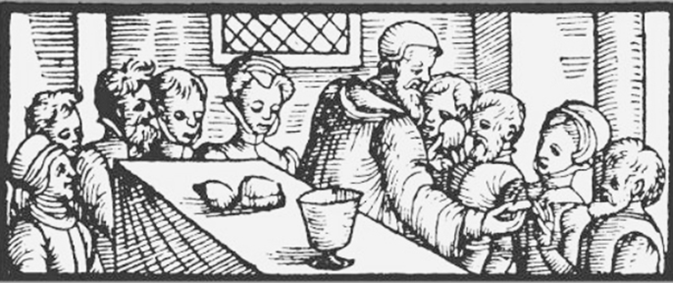

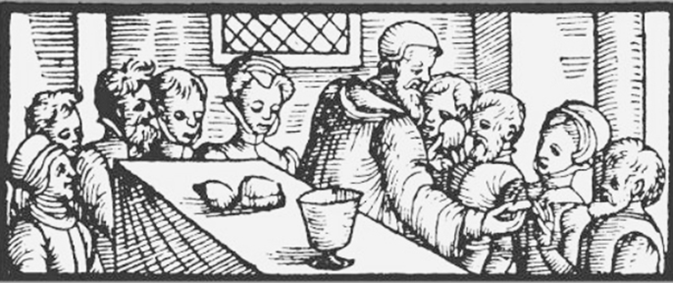

Taken together, and in an age when the individual’s relationship with God was becoming more and more central to Christian understanding, these rites emphasize the corporate and collective work of the Church, since the formation of Christian identity, belief, and practice is here understood to be conducted in and through the public, corporate worship of the Church. This emphasis is visible, especially, in Thomas Cranmer’s 1552 revision in the Book of Common Prayer, when he replaced the moment of the priest’s elevation of the consecrated host with the distribution and reception of the consecrated elements of communion by the congregation.

Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century theological arguments about the presence of Christ in the Eucharist were inevitably shaped by efforts to distinguish the Reformers’ position from that of Catholic tradition, that in the prayer of consecration said by the priest the substance of the bread and wine were transubstantiated into the Body and Blood of Christ. In this understanding, Christ’s presence is located physically, at a moment in time (the end of the recitation of the words of institution), and in a particular place (in the hands of the celebrant as he raises the consecrated elements for adoration by the congregation) and as the work of one person (the consecrating priest) acting before an essentially passive congregation.

Celebration of Mass, Elevation of the Consecrated Host. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Theological discourse about the meaning of this moment – static descriptive accounts of the Real Presence of Christ in the consecrated bread and wine – are descriptive of this moment, this moment alone among the long sequence of acts scripted by the text of the Mass. To use a theatrical metaphor – appropriate, since liturgical worship involves people wearing distinctive clothing who play specific assigned roles in the enactment of a scripted event — in this tradition of worship, the priest is the performer, God is the prompter, and the congregation is the audience.

Focusing on this moment, while it reflects a high doctrine of Eucharistic presence – the consecrated bread and wine really and truly are the Body and Blood of Christ – also distances the event of which it is a part from the actual culmination of the story on which it is modeled. In Paul’s version of the story, of course, Jesus takes the bread, gives thanks, breaks the bread, and gives it to his followers with the instructions to “take and eat.” But by the late Middle Ages, a similarly high doctrine of human sinfulness had led to a situation in which obedience to this command of Christ was rare. Actual reception of the consecrated bread (but not the wine) by the laity required extensive lay preparation, codified in the rite of Penance, involving personal confession of one’s sins to a priest and the priest’s proclamation of absolution.

This distancing of the laity from active participation in the Mass culminated in a decree of the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 that the laity were required to receive Communion only once a year. In a sense, the elevation of the host by the consecrating priest for viewing by the congregation – accompanied by the ringing of bells to call the congregation’s attention to what the celebrant was doing – came to be a substitute for the congregation’s regular active participation in the Eucharistic feast. Those of us familiar with Eamon Duffey’s classic study The Stripping of the Altars will surely remember his account of people moving around inside a church or even running from church to church while priests at multiple altars were fulfilling their obligation to celebrate the Mass daily so that layfolk could see as many elevations of the consecrated host as possible.

Celebration of Holy Communion, Distribution of the Consecrated Host. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

The significance of Cranmer’s deletion of the elevation of the consecrated bread and his moving the congregation’s reception of the consecrated bread to follow directly after the priest’s recitation of the narrative of Jesus’ Last Supper with his followers can now be more fully appreciated. Here, Cranmer clarifies for us that the rite enables the congregation to participate in Communion with Christ, not by simply observing a representation of Christ’s sacrifice on Calvary in the elevation of the consecrated Host, but by participation through time in the entire action with the bread and wine, or as one of the late 16th century commentaries on the Church of England’s Catechism put it, through “Bread and Wine, together with the actions of blessing, breaking, distributing and receiving, exercised in and about the same.”

Cranmer’s 1552 rite affirmatively locates the meaning of the Eucharistic celebration away from what is signified by the brief moment of elevating the consecrated host. Instead, it is to be found in the full process through time of priest and congregation as they jointly participate in the action of “blessing, breaking, distributing and receiving” the bread and wine of communion.

This understanding of the way Christ is present in the Eucharist has been aptly described by Christopher Irving as “a transposition of a sense of “real presence” to that of “real participation.” In this view it is through the work of the people of God, embodied in the priest’s and congregation’s actions of “blessing, breaking, distributing and receiving, exercised in and about the same,” the relationship between the bread and wine of communion and the congregation of participants is clarified, since both become “the Body of Christ for the Body of Christ.”

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Altar Area from Above. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

Cranmer articulates his understanding of “real participation” in the prayers at the end of his Communion Service. “Offering” and “Sacrifice” are here understood in terms of corporate action — “here we offer and presente unto the, O Lord, our selves, our soules, and bodies, to be a reasonable, holy, and lively sacrifice unto the, humblye beseching the, that al we which be partakers of this holye communion, may be fulfilled with thy grace, and heavenly benediction.”

Through a series of liturgical actions scripted by the Prayer Book’s texts, the congregation becomes one Body, both really and aspirationally, for Cranmer. Or, as he puts it, “thou doest vouchsafe to fede us, whiche have duly received these holy misteries, with the spiritual fode of the moste precious body and bloude of thy sonne, our saviour Jesus Christ, and doest assure us therby of thy favour and goodnes towarde us, and that we be very membres incorporate in thy mistical body, whiche is the blessed company of al faithful people, and be also heyres through hope of thy everlasting kingdom.”

Cranmer also abolished the need to go through the act of private confession and receiving of absolution for one’s sins before receiving communion; instead, he made as part of the Communion rite of 1552 – and in all subsequent versions of the Book of Common Prayer — a public confession and receiving of absolution situated in the rite as corporate and public preparation for the celebration of Holy Communion and the congregation’s receiving of the consecrated bread and wine.

The Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project enables us to experience the rites of Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer as embodying a theology of Eucharistic meaning found not in a moment of time but in an unfolding of events through time, participated in by clergy and laity who collaborate to reenact all the characters, roles, and events involved in biblical accounts of Jesus’ Last Supper with his followers. To continue our use of a theatrical metaphor, in this tradition of worship, the congregation is the performer, the priest is the prompter, and God is the audience.

The Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project thus addresses issues raised by emerging fields of study and practice such as digital archaeology, data visualization, historic acoustic reconstruction, recreation of soundscapes, material culture studies, historical geography, liturgical studies, and material religious studies. These fields seek to recover the experience of past time through integrating data about ephemeral and material events and practices into forms of presentation that enable students of the past to explore the changing past from multiple perspectives and in simultaneous narratives.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Ceiling. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

The Cathedral Project also addresses ongoing issues in a number of traditional and developing academic disciplines. These include English Reformation history, where revisionist historians’ emphasis on theological debates among Church elites, including the faculties at Oxford and Cambridge, as well as their use of continental sources for defining the Reformed tradition, ignore the content and significance of daily worship in the nations’ cathedrals and collegiate and parish churches. These fields also include the work of literary scholars who have sought to fit major writers like Donne and Herbert into preconceived understandings of one or another theological or spiritual tradition rather than attend to the formative reception of worship and the reading of biblical texts that structured the daily content of these writers’ own devotional lives.

The Virtual Cathedral Project, however, provides us with new tools for research into these issues by enabling us to experience the rhythms of set texts and variable readings that defined and structured the hours of each day and the seasons of the Church year. We are able to glimpse more fully the structuring experience provided by Cranmer’s reinterpretation of liturgical worship, the context, for example, for Walton’s account of George Herbert’s daily practice of conducting his observation of the Daily Offices:

“Mr. Herbert’s own practice . . . was to appear constantly . . . twice every day at the Church-prayers, in the Chapel. . . strictly at the canonical hours of ten and four,” joined by “most of his parishioners, and many gentlemen in the neighbourhood, constantly to make a part of his congregation twice a day: and some of the meaner sort of his parish . . . would let their plough rest when Mr. Herbert’s Saint’s-bell rung to prayers, that they might also offer their devotions to God with him.”

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Choir Screen. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

Yet we know today that – especially in the world of religious practice and devotion to the sacred — old habits die hard. In spite of Cranmer’s efforts to increase the frequency of lay folk receiving communion, the best the Church of England was able to achieve by the middle of the 17th century was to insist that the number of times people were expected to receive Communion be expanded from one time a year to three times a year. This, even though the Prayer Book contains an “exhortation” which the curate is to read “at certain times when” he “shall see the people negligent to come to the Holy Communion.” In this exhortation, the curate instructs his congregation that he calls “you in Christ’s behalf,” that he exhorts “you as you love your own salvation, that ye will be partakers of this Holy Communion.”

But perhaps it was the language of an exhortation that the rubrics require to be read at every Communion service, in which the curate insists that while “the benefit is great, if with a truly penitent heart and lively faith we receive that holy Sacrament . . . so is the danger great if we receive the same unworthily.” “For then,” he is scripted to say, “we be guilty of the body and blood of Christ . . . We eat and drink our own damnation. We kindle God’s wrath against us.” In any case, it would take 400 years and another liturgical revolution or two for Episcopalians in the United States and Anglican churches in England and in other countries to have the communion service as the main service on Sundays. It is especially sobering to remember that the official Book of Common Prayer for the Church of England is still the one adopted by the Church and Parliament at the time of the restoration of the monarchy in 1662.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the South Aisle of the Nave, Looking Westward. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

ESSAY 3. Inventing John Donne: Temptations of the Biographer

A Cautionary Tale in Honour of the 400th Anniversary of the Consecration of Trinity Chapel at Lincoln’s Inn on May 23rd, 1623, and Donne’s Sermon preached on that Occasion

This paper was delivered at the meeting of the John Donne Society at the Louisiana State University in 2023

The subject of this essay is the role of fiction in the biography of the priest and poet John Donne. Biography as a form is necessarily artificial. In the end, all biography is a form of fiction. Donne lends himself well to writers of biography; there is a great deal about his life that we do know, at least in comparison to the life of his slightly older contemporary William Shakespeare.[1] And, there is, of course, his work, much of which is occasion-specific, from his poems lamenting the death of Elizabeth Drury, the first of which was published in the year following her death in 1610, to his sermons preached on very specific occasions and in particular locations, and his Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, published in early 1624, only a few months after he experienced the illness that precipitated its composition.

Trinity Chapel, the Interior, looking eastward in 1623. Rendering by Jack McManus.

Many biographies of Donne have appeared over the years, beginning with Isaak Walton’s Life of Donne (1640), only 9 years after Donne’s death in 1631. But interest in Donne spurred by the early 20th century’s recovery of the metaphysical poets has led to a series of Donne biographies beginning in the later 20th century. Basic to this list is R. C. Bald’s magisterial John Donne: A Life of 1970, followed only a decade later by John Carey’s John Donne Life, Mind, & Art of 1981.[2] This momentum has continued in the 21st century, with David Colclough’s John Donne’s Professional Lives (Brewer, 2003) and John Stubbs’ John Donne: The Reformed Soul (Norton, 2006). Yet the interest in Donne’s life continues to grow, if the enthusiastic reception awarded the latest biography of Donne — Katherine Rundell’s Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne (Farrar Strauss & Giroux, 2022) — is any indication.[3]

The role of fiction in Rundell’s biography will be the chief concern of this essay, but before getting to it, I want to consider briefly current understandings and best practices concerning the issue of what latitude a biographer has in reimagining the subject of a biography. On the one hand, I think we recognize that a responsible biographer is called upon to create a coherent narrative of an author’s life, not simply to arrange the surviving data into a chronological list. We also recognize that in creating this narrative, a biographer must interpret the surviving data concerning the author’s life, and that there are gaps in the data to be reckoned with, works by the author to be interpreted, and conclusions to be drawn.

Therefore, we must acknowledge, even biography, with its goal of telling the truth about an author’s life, will contain what we must acknowledge as fiction. Biography therefore comes to reside within an artful but paradoxical conversation between the known and the imagined. Thus the critic Craig Brown is led to quote admiringly Peter Ackroyd to the effect that while ““Fiction requires truth-telling . . . in a biography one can make things up.”[4] But Brown is also compelled to acknowledge the value of data; he says in the same essay that the biographer “is at the mercy of information,” even though, he writes, “information is seldom there when you want it.” Therefore even Brown, while he affirms the reality that biography necessarily has a fictional dimension to it, also agrees with the biographer Mary Purcell, who in her essay “The Art of Biography” reminds us that the biographer “must discipline himself as a craftsman; he has to control his imagination for he may not stray beyond the limits the factual evidence at his disposal imposes upon him; his skill at his craft will show in the selection and interpretation of his material.”[5] Or, as Natalie Zemon Davis put it in her reconstruction of the life of Martin Guerre, what the biographer offers is “in part invention, but held tightly in check by the voices of the past.”[6]

Trinity Chapel, looking Northward. Rendering by Jack McManus.

Brown, Purcell, and Davis agree that when we are dealing with what Brown calls “the slippery art of biography,” we must recognize both the inevitability and the limits of fiction’s role. With that as background, we turn to Katherine Rundell’s new (and prize-winning[7] and highly lauded by the early reviewers) biography of John Donne. Rundell begins Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne, by asserting the claim[8] that the “power of John Donne’s words nearly killed a man.”[9] This dramatic event took place, according to Rundell, in the “late spring of 1623, on the morning of Ascension Day,” when Donne “had finally secured for himself celebrity, fortune and a captive audience.” “[H]is preaching was famous across the whole of London,” Rundell tells us, and, as a result, “Word went out: wherever he was, people came flocking, often in their thousands, to hear him speak.”

This day, according to Rundell, Donne preached at Lincoln’s Inn, “where a new chapel was being consecrated.” The way Rundell states these two facts, oddly, makes no connection between Donne’s preaching and the chapel’s consecration service. In her account, it is as though Donne woke up that morning in the Deanery at St Paul’s, made a decision to take the ”fifteen minutes’ easy walk across London,” and decided to preach. Still, she says, on a day when a chapel consecration was going on, people “came flocking.” As she tells it, this sermon must have been delivered outside this chapel, since, as we will see, Trinity Chapel had pews, and, Rundell tells us, while Donne was preaching his sermon, the crowd “pushed closer to hear his words,” a move difficult to make when people are seated in pews.[10]

Trinity Chapel, looking Westward. Rendering by Jack McManus.

As a result, Rundell says, “men in the crowd were shoved to the ground and trampled.” Note well, “to the ground,” not to the floor, yet another indication that Rundell imagines Donne’s sermon taking place outside the Chapel, or at least separate from the consecration service for the chapel. Yet, she goes on, doubling down on her claim that when “Two or three were endangered, and taken up for dead,” it was during Donne’s sermon. But, she assures us, “There’s no record of Donne halting his sermon; so it’s likely that he kept going in his rich, authoritative voice as the bruised men were carried off and out of sight.”

This opening scene, so vividly realized by Rundell, even though it is only 2 pages long, is sufficiently dramatic and compelling to have caught the special attention of several of the authors of laudatory reviews of Rundell’s work. Adam Kirsch, in the New Yorker, interprets Rundell’s account to mean that the crowd’s “press and thronging . . . led to a stampede.”[11][12] Rowan Williams, in the New Statesman, begins his review by noting that while the “last thing that keeps contemporary Anglican preachers awake at night is the risk of serious injury resulting from the crush of people in their congregations,” but Williams asserts, “Rundell reminds us . . . the risk was real enough when John Donne was in the pulpit.”[13] Catherine Nicholson, in her London Review of Books review, makes the most of Rundell’s claims: describing how “Rundell conjures the scene on a Sunday morning in April 1623, when Donne ’delivered a guest sermon in the new chapel at Lincoln’s Inn.’” Nicholson elaborates dramatically on Rundell’s own dramatic elaboration:

The chapel building filled, and over-filled, with what a contemporary report described as ‘a great concourse of noblemen and gentlemen’. As the crowd pressed forward to hear Donne speak, the situation grew dangerous; in the ‘extreme press and throng’, men stumbled and fell, or perhaps they simply couldn’t breathe: ‘Two or three were endangered and taken up for dead at the time.’ As Rundell observes, ‘there’s no record of Donne halting his sermon; so it’s likely that he kept going in his rich, authoritative voice as the bruised men were carried off and out of sight.’[14]

Trinity Chapel, Pew Ornaments. Rendering by Jack McManus.

There is, indeed, no record of Donne’s halting his sermon.[15] Nor, as we will see, is there any record of Donne’s being interrupted during his sermon, nor that anyone was shoved to the ground (or the floor) during his sermon, or that the crowd present on that occasion came expressly to hear Donne, or, in fact, that any of the events of that May 22nd, 1623 unfolded in the way Rundell describes them. Or that most of them ever happened at all. Unfortunately for Rundell’s approach to writing Donne’s biography, the one occasion in John Donne’s life for which there is a remarkably abundant supply of data happens to be about his role in the events of the morning of Thursday, May 22nd, the Feast of the Ascension in 1623, at Lincoln’s Inn. May 22nd in 1623 was the date chosen by the Inn for the consecration of its newly-constructed Trinity Chapel, opening it officially for use as a worship space by the members of the Inn.

Four reports detailing this worship service, and its setting in time and space have survived. They include two lengthy and detailed accounts now preserved in the Archives of Lincoln’s Inn. One of these was written by a Fellow of Lincoln’s Inn;[16] the other, bearing his official seal, is Bishop Montaigne’s official account of his actions in consecrating the Chapel.[17] In addition to these two extensive accounts we also have 2 brief summaries of the day’s events;[18] one (also written by a member of Lincoln’s Inn) is now in the possession of the Society of Antiquaries, dated “Assencion Day 1623,” and the other is one of John Chamberlain’s letters to Sir Dudley Carleton, dated a week later, on May 30th, 1623.[19] When taken together, these four documents provide us with a detailed, almost moment-by-moment description of the Service of Consecration for Trinity Chapel that did take place on May 22nd, Ascension Day, in 1623.[20]

Trinity Chapel, 1623. Rendering by Jack McManus.

All four of these documents are in essential agreement about what took place on that morning in late May at Lincoln’s Inn. The two longest accounts give us the fullest amount of detail. To summarize what they tell us — this service, led by George Montaigne, the recently-consecrated Bishop of London, lasted from 8:00 AM until 11:00 AM on the morning of May 23, 1623. The service started outside the Chapel, on the landing in front of the doorway to the Chapel, where a crowd had gathered, assembled on the ground in front of the Chapel.

Rundell’s description of the events at Trinity Chapel on Ascension Day is of course dependent on her belief that the number of attendees at the Consecration ceremony was both large and boisterous. But the only direct comment in any of these accounts about the size of the crowd is found in the anonymous account of the Consecration now in the archives of the Society of Antiquaries. To this observer there was a “Concourse & Confluence of people,” but he goes on to say that it was smaller than in should have been, since “The Kings Councell vppon especiall Command sate that Day att white Hall, soe that only ye Bishop of London two Iudges & foure sergeants were ye men of (quality) that were present att ye Consecration.”[21]

Furthermore, those in attendance were not random Londoners who “came flocking” to hear Donne preach, but were – in addition to a few members of the Royal Court[22] — chiefly members of England’s legal community – Justices of England’s highest courts, lawyers, members of Lincoln’s Inn, and law students aspiring to become barristers, people described repeatedly in these documents as “worshipful and venerable men,” men accustomed to behaving “decently and in good order.” These were definitely not the kind of folks Rundell imagines as having “flocked” to hear Donne preach, pushing and shoving to get closer to him.

We are then told that[23] “the reverend father in Christ [George Montaigne, Bishop of London], accompanied by many reverend and venerable men, approached the doorway of the chapel to be consecrated, and to him the venerable men Thomas Spenser, Richard Digges, and Egidius Tooker, esquires, . . . and William Ravenscroft, one of the worshipful counselors of the aforementioned Inn, indicated that they had . . . seen to the erection and equipment of the said chapel, on their own private grounds and with their own private funds. And they yielded their rights in the same, and so . . . they granted, gave, and donated the aforesaid chapel to God almighty and to the highest, holy, and indivisible Trinity, and . . . they presented and handed over the keys of the aforesaid chapel to the same reverend, humbly beseeching the said reverend father to declare and consecrate the aforesaid chapel to the everlasting honor and service of God almighty, and the use of those staying in the aforesaid Inn.”[24]

Trinity Chapel, Lincoln’s Inn (1623). Image courtesy Lincoln’s Inn.

Bishop Montaigne and Thomas Wilson, his chaplain, then entered the building, offered prayers, then turned to “the congregation still standing at the doors of the chapel” and read a lengthy statement which the Inn’s Fellow claims formed the actual moment of consecration. Only then was “the whole congregation . . . called together into the chapel.”[25]

What followed on that day, once everyone was in the Chapel, was the sequence of services prescribed for Sundays and Holy Days, like the Feast of the Ascension in parishes, collegiate churches, and cathedrals across England – Morning Prayer, with its readings set by the Prayer Book’s lectionary, followed by the Great Litany and Holy Communion, with a sermon, a sequence of events that filled the 3-hour span between 8:00 and 11:00 AM.[26] In this service Donne’s sermon followed the Great Litany rather than coming after recitation of the Nicene Creed in the Communion Service, but otherwise the service was what was provided for, prescribed for use, and scripted by the Book of Common Prayer. Afterwards, Bishop Montaigne tells us, he went downstairs to consecrate the building’s undercroft for use as a burial ground for Fellows of Lincoln’s Inn. When the service was over, some three hours after it began, everyone retired to the Inn’s ancient Great Hall, directly adjacent to the new Chapel, for a festive reception.

And so we leave them, at least for the moment, celebrating the accomplishment of the Fellows of Lincoln’s Inn in raising the money and seeing through to completion and consecration of Trinity Chapel. For us, however, the most important point to note here is that, unlike Rundell’s account, we now know that Donne’s sermon was not a stand-alone event that happened to take place on the day Trinity Chapel was consecrated, but an integral part of that larger service. We also need to recognize that nowhere in either the Fellow’s account or Bishop Montaigne’s account of events – the two longest and most detailed of all these accounts – is there any mention of the “Two or three [who] were endangered, and taken up for dead.” Nor do any of our contemporary witnesses report that the congregation was unruly, or that Donne’s sermon was interrupted, or that anyone rushed forward to get closer to him.

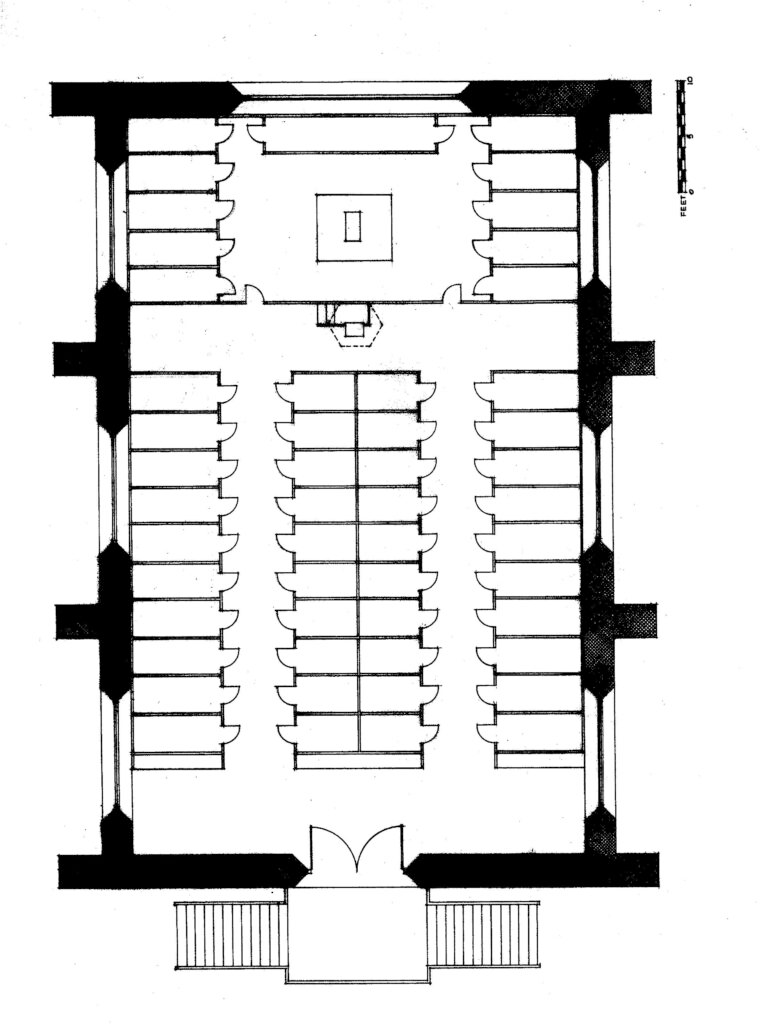

Trinity Chapel, Floorplan (1623). Image crafted by Eugene W. Brown, AIA.

One is therefore left with the conundrum of understanding where Rundell found data or inspiration from which to extrapolate, or, perhaps better put, to fabricate, her account of this ceremony. The answer – to the extent there is an answer – lies in the other two of our sources — the anonymous account now in the possession of the Society of Antiquaries, which was written by a member of Lincoln’s Inn on Ascension Day itself, and the letter John Chamberlain wrote to Sir Dudley Carleton a week later. The Society of Antiquaries’ document, written on the day of the event, brings us closest to what actually happened. Our anonymous author says,

“Vppon Thursday beinge Assention Day was ye Chappel of Lincolnes Inne Consecrated, where there was such a Concourse & Confluence of people that Sr Francis Lee was soe thronged that hee fell downe deade in ye presse, And was Caryed away into a Gentlemans Chamber & wth much a doe Recouered.”[27]

So, we now have an eyewitness account of the Consecration which includes a description of the crowd’s behavior as “a Concourse & Confluence of people,” although we must note this account does not describe the crowd as pushing and shoving. According to this account, the number of people who reacted adversely to the behavior of the crowd is down to one. So we learn that one person fainted – in the terminology of the day, he “fell downe dead in the presse” — and we have his name – Sir Francis Lee – and we know the author of this account believed that Sir Francis Lee fell because he was “soe thronged” by the crowd.

The Book of Common Prayer (1604), Title Page. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

This narrator then moves on, chronologically, to describe what happened next; his account replicates, albeit more succinctly, the account given by the Fellow of Lincoln’s Inn in his account. “The manner of itt (i.e. of the Consecration Service) was in this Manner./ First ye Bishop himselfe alone wth Wilson his Chaplayne entredd ye Chauncell.” Then we get a description of the prayers Bishop Montaigne prayed, and things he did, repeating information we find in the Inn’s Fellow’s account. Eventually we are told, “This beeinge done ye Mynister beganne Devine service & reade ye 24.27 & 28 psalmes, And for ye Chapters ye i of Kinges 8. & Iohn ye 10th, And then ye Letanye & soe to ye Sermon, where Doctor Doone preached & tooke for his Text a scripture out of Iohn.”

Folks familiar with the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer will recognize that “Divine Service” means the Office of Morning Prayer, which consists of Prayers, Anthems, Versicles and Responses, readings from the Book of Psalms (on this day Psalms 24, 27, and 28), a full chapter from the Old Testament and another from the New Testament – at least 45 minutes of reading – followed by the Great Litany, with its extended set of prayers (at least another half an hour), and only then do we get to “the Sermon, where Doctor Donne preached.” Furthermore, the service was not over when Donne finished his sermon; instead it went on for another hour, completing the sequence of Prayer Book worship on Holy Days with a service of Holy Communion.

And, nowhere, in this detailed account by an eyewitness, from its opening comments about Bishop Montaigne’s actions at Trinity Chapel’s doorway through its list of the Order of Service, and its comments on Donne’s sermon, is there any further mention of the fate of Sir Francis Lee. It is very clear from the sequence of events contained in this account that Lee’s collapse must have taken place before the Consecration service, when the congregation was first gathering in the Chapel’s churchyard and crowding around the steps up to the landing outside the Chapel’s door, while awaiting the appearance of Bishop Montaigne, at 8:00 AM, and not, as Rundell argues, at least an hour and a quarter later, after the crowd had entered the building and dispersed itself among the Chapel’s array of seating and standing room.

Trinity Chapel, Lincoln’s Inn. Rendering by Jack McManus.

Then, this writer goes on to describe the Consecration service itself as having proceeded exactly as our other sources describe it, again with no mention at all that Sir Francis Lee passed out during the service itself or that the service – or Donne’s sermon – were interrupted in any way. So, we may infer that the behavior of the crowd of judges, lawyers, and members of the nobility that might have caused Sir Francis Lee to pass out took place outside Trinity Chapel, while the crowd was assembling and awaiting the arrival of Bishop Montaigne and his entourage so the service could begin.

Or, perhaps, Sir Francis’ collapse could have happened when the congregation was invited by Bishop Montaigne to enter the building after he had offered his prayers inside. But I personally am betting on the gathering time – these folks knew how to process in an orderly fashion and probably did so as they filed into the Chapel. Supporting this argument is the fact that the seating area inside the Chapel was divided into sections and assigned to different categories of members of Lincoln’s Inn – one area allocated to senior members, another area to the broader membership, and yet another area to those preparing for entry into the legal profession. So the majority of those waiting to process into Trinity Chapel would have known where they were headed and would have organized themselves accordingly, knowing that their assigned seats were waiting for them.[28]

Only when we turn to the letter John Chamberlain wrote to his friend in the Hague on May 30th, a week after the Consecration ceremony at Trinity Chapel, do we find the original source for Rundell’s quotations about these events and the starting point for her speculations. In his letters to Sir Dudley Carleton, Chamberlain consistently seeks to keep his friend informed about events in London and especially in Court, as well as about the topics of conversation among their friends. Following his usual pattern, Chamberlain’s letter of May 30, 1623, includes lots of court news, especially concerning the state of King James’ efforts to achieve the Spanish Match for his son Charles. At this point in that long narrative of frustration, Chamberlain expects that the negotiations are going well, and that “We look daily to heare of the solemnization of the marriage.”[29] As part of those preparations, Chamberlain notes that a week ago “the Spanish ambassador laide the foundation or first stone of the chappell that is to be built at St. James for the Infanta.”[30]

Donne’s Encaenia Sermon, Title Page. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Then, almost as an aside, or perhaps as a contrast to the construction of a chapel intended for Roman Catholic worship, Chamberlain says, of a chapel intended for worship according to the Book of Common Prayer, “Lincolns Ynne new chappell was consecrated with more solemnitie by the bishop of London on Ascension day, where there was great concourse of noblemen and gentlemen wherof two or three were indaungered and taken up dead for the time with the extreme presse and thronging.”

In Chamberlain’s account of the events of Ascension Day at Trinity Chapel, the story told by the anonymous member of Lincoln’s Inn goes through some subtle but nevertheless significant changes. The anonymous writer’s description of “Concourse & Confluence” has become an “extreme presse and thronging” and the unfortunate Sir Francis Lee has become “two or three [who] were indaungered and taken up dead.” Chamberlain then goes on immediately to say that “The Deane of Paules made an excellent sermon (they say) concerning dedications.” Thus Chamberlain’s account, unlike all the other accounts of the events at Trinity Chapel, there is no mention of the hours of worship services that preceded and followed Donne’s sermon. But Chamberlain’s insertion of the words “they say” shows us that he was actually not there, that his account of events was dependent on hearsay evidence. So, Chamberlain’s version, based on other people’s accounts, suggests that in the days after the Feast of the Ascension the story both lost some aspects of the story but also grew in detail in some of its specific as stories passed through oral transmission are often likely to do.

Rundell’s overall account of Donne’s activities on Ascension Day in 1623, plus her use of Chamberlain’s language and tone and her direct quotes – especially her use of Chamberlain’s phrase “Two or three were endangered, and taken up for dead”[31] – make clear that Chamberlain’s letter to Sir Dudley Carleton is her source for what Donne was about at Lincoln’s Inn on the Feast of the Ascension in 1623.[32] What Rundell has done is to continue the process of elaborating on the events of May 23rd 1623, begun by John Chamberlain when he expanded the number of gentlemen who collapsed while the crowd waited to be admitted to the Chapel from one (Sir Francis Lee) to “two or three,” a process continued by Adam Kirsch, in his New Yorker review when he interprets Rundell’s account that “men in the crowd were shoved to the ground and trampled” to mean that the crowd’s “press and thronging . . . led to a stampede.”

In spite of Rundell’s belief that the consecration of Trinity Chapel was yet another opportunity for Donne to dazzle the congregation with his preaching style, all accounts of the service make clear that the reason for the gathering of a congregation at Trinity Chapel was for the Consecration ceremony. Donne, then Dean of St Paul’s, was chosen as preacher for the occasion not because he was a celebrity preacher, as Rundell claims, but because he had been involved in the process of planning and constructing Trinity Chapel from the beginning. Donne had served as the official Preacher for Lincoln’s Inn from 1616 until his appointment as Dean of St Paul’s in 1621. He had supported plans to build the Chapel, had preached at least one sermon encouraging the Inn to undertake its construction, been instrumental in raising funds to support the project, and had laid the cornerstone for construction of the building. He contributed his own funds to the construction, a gift marked by a part of the program of stained glass, which, loosely translated, reads, “I, John Donne, Dean of St Paul’s, caused this to be made.”

Donne’s contribution to the building of Trinity Chapel. Image courtesy John N. Wall

In fact, far from being a sermon that would enhance Donne’s reputation as a preacher for a wide general audience, Donne’s sermon is very much about the chapel itself, and very much directed very personally to his former colleagues at the Inn. He starts by reminding them of how little money they had for the project at its beginning, and what a significant accomplishment it was that it is now complete and being put into service. His sermon is about what makes a building holy, which turns out to be the worship that takes place within it, the very worship that they are all involved in at that moment, and the members of the congregation who gather inside it to take part in that worship:

“This Festivall belongs to us, because it is the consecration of that place, which is ours . . . But it is more properly our Festivall, because it is the consecration of our selves to Gods service. . . . Your Bodies are holy, by the inhabitation of those sanctified Soules. . . These walles are holy, because the Saints of God meet here . . . But yet these places are not onely consecrated and sanctified by your comming; but to bee sanctified also for your coming; that so, as the Congregation sanctifies the place, the place may sanctifie the Congregation, too.[33]“

As our anonymous reporter of the event describes it, Donne’s point is that use of the Chapel in “prayer preachinge Administration of ye Sacrament of ye Bodye & blood of Christ, And singinge of Hymnes & psalms” that really consecrates a place of worship. But the worship by the congregation in this space is not an end in itself but a consecration of the worshippers to God’s service. Interestingly, our anonymous writer thought Donne’s sermon showed “superficiem but not Medullam Theologiae haveinge Eloqentiae satis but sapientiae parum,(that is, it showed the surface rather than the marrow of theology, having sufficient eloquence but little wisdom.” So much for Rundell’s claims about Donne’s having a universally positive reputation as a great preacher!

My point is, the crowd came to Trinity Chapel because it was a new church building (a rare thing in early 17th century England), because many of those present had contributed to its construction, and because it was at Lincoln’s Inn, an important part of the London legal and courtly worlds. Donne was the preacher because he had been involved in the construction of Trinity Chapel from the beginning and because he was the hometown boy who had made good by becoming Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral. Thus, his sermon was not about demonstrating the glories of his preaching skill or satisfying a devoted audience who followed him wherever he preached, but about the occasion, about the act of consecration, about how the worship being done in that place and time by the people who showed up for that service functioned as consecration, setting Trinity Chapel apart from a secular to a holy purpose.

Lincoln’s Inn, the Old Hall, looking south, Site of the post-Consecration Reception. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

The historian Lewis Namier comments on the work of historians and on the temptations they face. “One would expect people to remember the past and imagine the future,” he writes. “But in fact, when discoursing or writing about history, they imagine it in terms of their own experience… they imagine the past and remember the future.”[34] Donne surely would have been unhappy with Rundell’s treatment; the past she imagines for him in her biography sets him apart from his community, makes his distinctiveness as a person about his showing off, praising him for what she sees as achieving personal gain and cultural prominence. Donne, in his sermon for Ascension Day in 1623, was about giving meaning to the occasion and giving thanks for what the Lincoln’s Inn community had achieved, about understanding how the building they were inside of was both fulfillment of their aspirations and challenge to make good on the building’s promise to enrich the life of the community and to further the larger goals of Christian living. One hopes Sir Francis Lee recovered from his collapse quickly enough to hear it.

The Notes for ESSAY 3 are found in SECTION 5, at the bottom of the COMMENTARY section, see below.

An earlier version of this essay was published in the journal Renaissance Papers 2023, pp. 123-137.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

St Paul’s Cathedral, the South Facade. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

ESSAY 4: “Very members incorporate”: Clergy and Lay Collaboration in the Space and Time of Prayer Book Worship“

This paper was delivered at the Donne and Architecture Conference at Oxford University in 2026.

Over the past decade, my colleagues and I have been using digital modeling tools to give us the experience of the sights and sounds of worship and preaching at worship services involving John Donne while he was Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral in the early 1620’s. Our goal throughout has been to achieve the highest possible degree of accuracy in replicating the original experience of these events. With the aid of scripts prepared in early modern London pronunciation by the linguist David Crystal performed by actors trained by him in that style of speaking, together with the talents of the Choir of Jesus College at Cambridge University, we were able to recreate several such occasions.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the West Front. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

We were also able to recreate the appearance of Trinity Chapel at London’s Lincoln’s Inn as it was on Ascension Day, May 23rd, 1623, the day it was consecrated by George Montaigne, then Bishop of London, a service in the context of which Donne, a former chaplain at Lincoln’s Inn, preached the sermon. (the Virtual Trinity Chapel Project). By that point in our work, however, our funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities had run out, so we were unable to recreate the sound of this service.

Trinity Chapel of course contains in one of its stained glass windows what is in effect John Donne’s signature, naming his own personal contribution to the construction of Trinity Chapel.

Donne’s contribution to the building of Trinity Chapel. Image courtesy John N. Wall

All three of these projects are now clustered under our umbrella site – the Virtual John Donne Project. However interesting these projects might be on their own, my purpose in this paper today is to illustrate some of the ways that these sites might be used to further our understanding of Donne’s role in the worship life of St Paul’s Cathedral and Lincoln’s Inn as the Church of England approached the one hundredth anniversary of its first break with the Papacy during the reign of Henry VIII.

These sites enable us to recognize that the bulk of Donne’s writing on religious subjects was done for delivery on specific occasions in specific physical places, and in the context of specific worship services scripted by the Book of Common Prayer. The Prayer Book rites in use at St Paul’s and in Trinity Chapel enabled congregations to participate in communion with Christ, not simply by observing a representation of Christ’s sacrifice on Calvary in the elevation of the consecrated Host by the presiding priest or bishop. Those of us familiar with Eamon Duffy’s monumental study The Stripping of the Altars will recognize that in late medieval worship, the primary actor was the celebrant. The congregation gathered to watch him perform the miracle of transforming the bread and wine of communion into the Body and Blood of Christ. As Duffy puts it.

[K]neeling congregations raised their eyes to see the Host held high above the priest’s head at the sacring . . .Christ himself, immolated on the altar of the cross, became present on the altar of the parish church, body, soul, and divinity, and his blood flowed once again, to nourish and renew Church and world.

In Duffy’s account, the actual participation of layfolk in the priest’s performance was primarily visual; Duffey in fact describes congregants moving from place to place to observe the elevation of the Eucharist host at as many altars as they could on a given day. Indeed, the late Medieval Church insisted that congregants actually receive the consecrated Host only once in a liturgical year. And, of course, the language of the service itself was in Latin, a language in which some members of the congregation may have been fluent but the majority of whom, especially outside London, Oxford, or Cambridge, were not.

Celebration of Mass, Elevation of the Consecrated Host. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

To use a theatrical metaphor, the priest is the performer, God is the prompter, and the congregation is the audience

In contrast, after the introduction of the Book of Common Prayer of 1552, the elevation of the consecrated host was replaced with the reception of the consecrated bread and wine by clergy and members of the congregation. In this arrangement, by the 1620’s, on all Sundays and 27 Saints’ or other Holy Days, the celebrant would recite the words of institution, the story of what Jesus and his disciples did with bread and wine on the night he was betrayed by Judas, and reception of the consecrated elements by clergy and laity would follow immediately. So the identification of the consecrated bread and wine as the Body and Blood of Christ was connected with recognition of the gathered community of the Church, the Body of Christ for the Body of Christ.

Celebration of Holy Communion, Distribution of the Consecrated Host. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Again, to use a theatrical metaphor, the congregation is the performer, the priest is the prompter, and God is the audience.

This affirmation of the meaning of congregational participation in Cranmer’s Communion rite suggests why Cranmer thought it appropriate to relocate the Gloria in excelsis to this point in the service so it can serve as a hymn of praise to God for the gifts that have been bestowed by participation in the Communion rite. A late sixteenth century commentary on the Church of England’s Catechism put it, Christ was received through “Bread and Wine, together with the actions of blessing, breaking and receiving, exercised in and about the same.” To reemphasize the belief that the meaning taken on by the bread and wine during the service of Communion is contingent on the Prayer Book’s directions for the conduct of the Communion service state that “if any of the bread and wine remaine [at the end of the service], the Curate shall have it to his owne use,” presumably for his lunch. This would change, of course, with time – by the adoption of the Prayer Book of 1660 only leftover bread that had not been consecrated was available for the Curate’s lunch.

Paish clergy – in a reaction against the medieval pattern of non-communicating celebrations of the Eucharist – were required to have at least four members of their congregations agreeing to receive communion with them for the celebration to continue in the service past the Intercessory Prayer. But, according to the rubrics, “in Cathedral or Collegiate Churches, where be many Ministers & Deacons, they shall all receive the Communion with the Minister every Sunday at the least.” So, we can safely assume that on the 79 occasions in the liturgical year when Holy Communion was celebrated at St Paul’s Cathedral, the morning’s order of worship would begin with Morning Prayer, followed by the Great Litany and the rite of Holy Communion in its entirety.

These liturgical changes had a profound effect on the use of space inside St Paul’s Cathedral. The Nave, which had been the site of religious processions and celebrations of Mass at side altars for the repose of the souls of the departed, was now converted from a sacred to a secular purpose, the site of Paul’s Walk, where the noble and wealthy layfolk paraded in their finest clothing.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Nave, looking East. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.